The N.C. Task Force for Racial Equity in the Criminal Justice System was established in June in the wake of widespread protests against police brutality and racism. It was established by Gov. Cooper and is made up of 24 people from a wide range of backgrounds. The task force will recommend policy changes and reforms of North Carolina’s criminal punishment system.

On September 15, CDPL’s Executive Director Gretchen M. Engel addressed a working group of the task force. These are her remarks.

Good morning and thank you for the opportunity to speak to all of you who have donated your time to work on these important issues. My name is Gretchen Engel and I’m the executive director of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation in Durham. I came to North Carolina in 1992, fresh out of law school, when Henderson Hill gave me a job in capital defense. Over the years, I had the good fortune to work with Mary Pollard as well.

One of my first death row clients was Quentin Jones. Quentin was 18 years old at the time of the robbery and murder that landed him on death row.

Seventeen years ago this August, I watched the State of N.C. execute Quentin. He was then 34 years old.

After his execution, I learned that one of the jurors in his case had been interviewed by researchers at Northeastern University in Boston, my alma mater. This is what the juror said about Quentin: He was a typical n—-r. You know, if he’d been white, I would’ve had a different attitude.

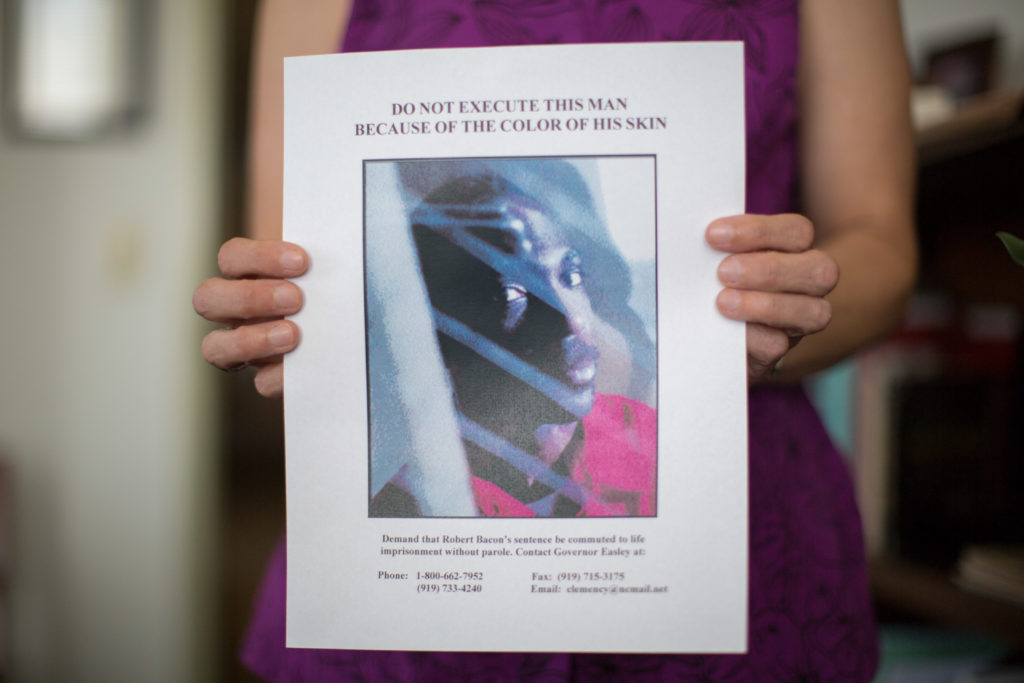

Another client of mine, Robert Bacon, was tried by an all-white jury for the murder of a white man named Glennie Clark. Robert’s codefendant, Bonnie Clark was white. Bonnie was married to Glennie Clark and she was having an affair with Robert. It was Bonnie’s idea to kill Glennie and she lured him to the site of his death.

This is what a juror told me about the sentencing deliberations in Robert’s case: Blacks commit more crime. It’s typical of Blacks to be involved in crime. He shouldn’t have been dating that white woman. He was wrong to do that. And he deserves the death penalty. Thankfully, the Governor commuted Robert’s death sentence to life.

After doing this work for nearly 30 years, and seeing countless examples like these, the racism of the death penalty is very real and very personal.

I was asked to talk about the cost of the death penalty. There are a couple of ways to think about cost. One is just to count up the money. Another is to think about what we get for the money. Dollars. Value.

We know the death penalty costs a lot of money. Dr. Phil Cook at Duke University did a study showing how much — $11 million a year. Note that Dr. Cook focused on defense costs. His estimate does not include resources the Office of the Appellate Defender and the North Carolina Supreme Court could devote to other things, the extra time spent by prosecutors in capital cases, or the costs to taxpayers for federal appeals.

So what are we getting for our money? Not a lot. North Carolina has nearly 140 people on death row. Almost 90 of them have been there for 10, 20, 30, or more years. In the past decade, we’ve sentenced only 11 people to death. Looking at the past decade, you’ll see that most years we’ve spent at least $11 million dollars to obtain one or zero death sentences. Meanwhile, our last execution was in 2006, 14 years ago.

Some would say justice is priceless. There is no price on justice. One question then is, how well does this system operate? I suggest to you that if the death penalty system were the airlines, no one would fly. We’d all be too terrified.

A national study of capital sentencing between1973-1995 looked at error rates in capital sentencing. Researchers at Columbia University analyzed nearly a quarter century of data, looked at appellate reversals for serious constitutional error. Nationally, the error rate was 68%, nearly seven out of ten. North Carolina’s error rate was 71%. Truly, the death penalty is the Ford Pinto in our criminal justice tool box.

Most disturbing is how wrong we get it. Henry McCollum spent more than 30 years on death row for a crime he did not commit. He and his brother Leon Brown were exonerated by DNA evidence in 2014. Because of Henry’s wrongful conviction, and the years it took to figure that out – thank goodness we didn’t execute him in the meantime – the family of Sabrina Buie, the 11-year-old girl who was killed, has never received justice.

Henry McCollum was one of 10 men wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in NC. The others were Sam Poole, Christopher Spicer, Alfred Rivera, Alan Gell, Jonathon Hoffman, Glen Chapman, Levon Jones, Henry McCollum, Leon Brown, and Charles Finch.

Nothing about the death penalty apparatus operates with surgical precision. Yet it is eerily good at targeting Black people. Eight of these 10 men were Black. One was Latino. Nine of 10 were people of color. Collectively, these men spent 155 years in prison for crimes other people committed.

Innocent people are disproportionately people of color. The same is true of other vulnerable populations. Of the people on North Carolina’s death row when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it was unconstitutional to execute people who committed their crimes as children, under the age of 18, three of four were Black. Of the people on our death row when North Carolina barred the execution of people with intellectual disabilities, 16 of 18 were people of color.

Chief Justice Beasley recently observed: In our courts, African-Americans are more harshly treated, more severely punished and more likely to be presumed guilty. The death penalty was conceived as punishment for the “worst of the worst.” Worst crimes, worst people. Most calculated and most cruel killings, committed by the most depraved.

Our “modern” death penalty was supposed to be rational, not arbitrary. Getting the death penalty was not supposed to be like being struck by lightning. And, actually, it isn’t. More often, it simply strikes people who are Black. Let’s look at marginal cases, cases that don’t seem to be the “worst of the worst.”

Consider the people on our death row even though they did not personally kill the victim. They were non-shooters, non-triggermen. Of the people who have been sentenced to death in North Carolina who were not the actual killers, four of four were people of color.

Consider the people on death row whom the jury found did not premeditate and deliberate the murder, people who were convicted only of felony murder. Seven of seven in this group are people of color.

Let me go back for a minute to what Chief Justice Beasley said about African Americans being more harshly punished. In fact, the Blacker you are, the more harshly you will be punished.

A 2006 study by Stanford University psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt showed that murderers with stereotypically “Black-looking” features are more than twice as likely to get the death penalty as lighter skinned Black defendants.

In 2001, when Robert Bacon had an execution date, I interviewed Bonnie Clark’s lawyer. The lawyer was a former prosecutor and a prominent civil lawyer when I spoke to him 13 years after Bonnie enlisted Robert in the plot to kill her husband. I asked him why he thought Bonnie got life and Robert got death. Here’s what he said: You know what I think happened? Robert Bacon is a very dark skinned black man, very dark skinned, pure Negro. She was white. The victim was white. To tell you the truth, that’s what I think happened, that’s what I think the jury thought about.

At the point he told me this, I hadn’t yet told him what the juror said about how Robert had no business running around with a white woman.

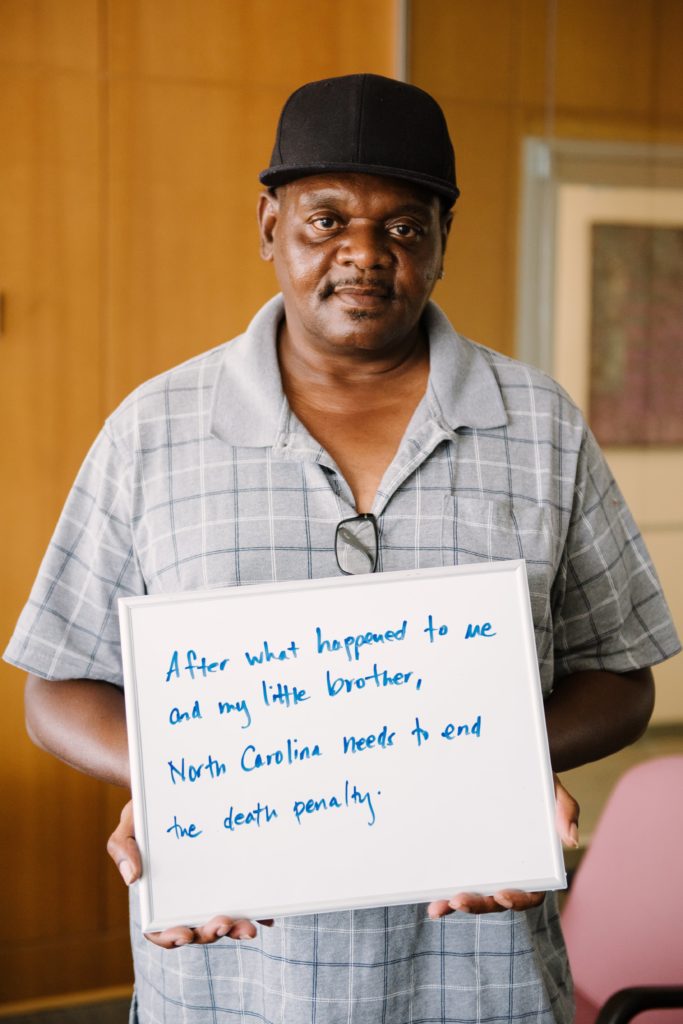

Shirley Burns had two sons. One of them is Marcus Robinson. When Marcus was 18, he killed a 17-year-old white boy. Marcus was sentenced to death. The other was Curtis Green. Curtis was murdered. Nobody went to death row for that murder.

When it comes to the death penalty, white lives matter. In 2016, FBI data showed the homicide rate for Black victims was nearly four times the national average and more than six times that of whites. Consistently, Black people make up the majority of murder victims.

But the death penalty is imposed as a punishment for killings of white people. A 2001 UNC study of homicides between 1993 and 1997 showed the odds of receiving the death penalty in NC were 3.5 times higher when the victim was white. A 2010 study by Michigan State University showed defendants charged with murder in NC from 1990 to 2009 were more than twice as likely to receive the death penalty if the victim was white.

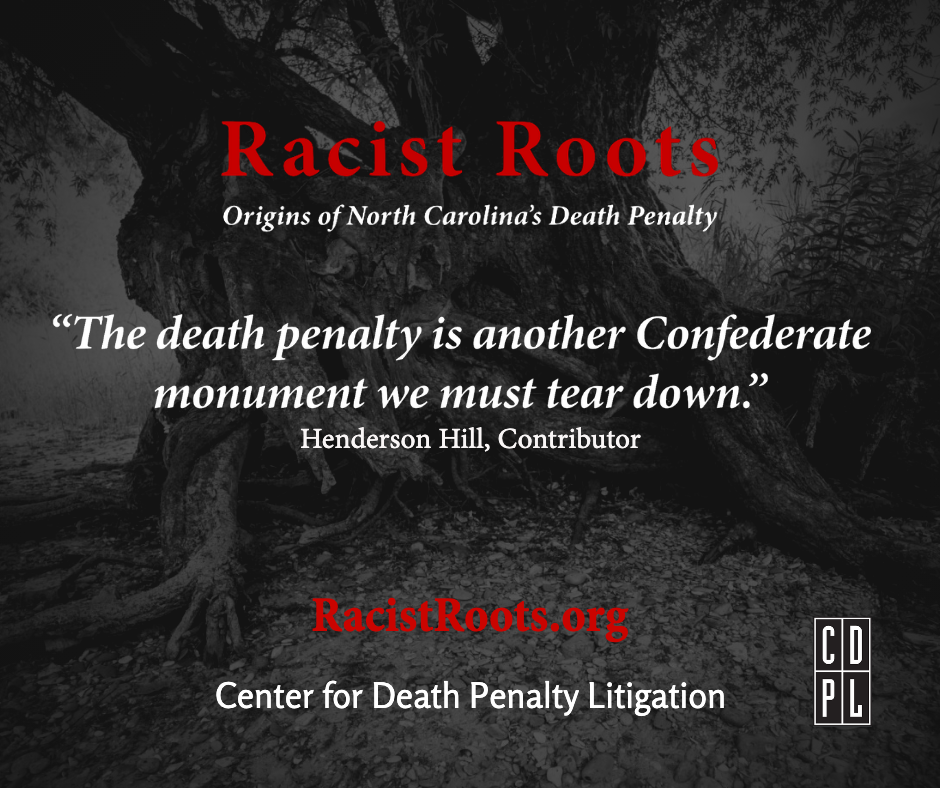

I wish what I’ve told you today were new. But it’s not. Today the Death Penalty Information Center released its report on the history of race and the death penalty. The title of the report is Enduring Injustice: The Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S. Death Penalty. Next month, my office will launch a web-based project called Racist Roots: Origins of North Carolina’s Death Penalty. What I’ve told you today is an old story. As Rev. Barber says, “The link between slavery, Jim Crow, lynching and the death penalty is as connected as the intertwined ropes of the lynchman’s noose.”

We are at a momentous time in our history. We have to ask ourselves, what do we value? The death penalty is irrevocable punishment. If we continue to tinker with it, we will execute an innocent person. How could we not?

The death penalty experiment in NC has been going on for more than 40 years. We’ve yet to come even close to eliminating the taint of race. It’s time. If we value racial equity, we cannot maintain the death penalty.